< < BACK TO CHAPTER IIIB - ISCORAMAS (1.5X)

DISCLAIMER: This article was written way before the announcement of the FM system. I haven’t had time to study it properly, so some information here is probably outdated already.

C – DOUBLE FOCUS (2X)

Entry point for many anamorphic users, these lenses are cheaper because they present a lot of challenges to work with. All of them are projection lenses, have an awesome 2x stretch, and placed on top of a taking lens. As they’re projection lenses – and the screen is NEVER close to the projection booth – it’s quite common that their minimum focus ranges between 6 to 9m.

The name of the chapter already introduces on of their challenges: double focus. In order to have a focused image it’s required to focus both the taking lens and the anamorphic block to the very exact distance. If one of them is slightly off, image quality degrades quickly.

Taking this into account, it’s easy to figure that camera movements and rack focusing are very complex operations to be executed during a single shot. The shooting style has to fit the lenses.

It’s a practical thing to split them in two main categories: 35mm projector lenses – large, heavy and, sometimes, colorful – and smaller projector lenses, like 8mm or 16mm, used in airplanes, military applications or film clubs.

The 35mm anamorphic projector lenses are still in production by Schneider Optics. There are vintage models made by Sankor, Bausch & Lomb, Carl Zeiss e Möller. Their main advantages are high image quality and sharness from edge to edge of the frame. Because of their minimum focus distance, diopters – close-up lenses – are essential extras to use these lenses in narrative films (6m to achieve focus is pretty far for anything with a low budget). Besides, due to their weight, a proper support system is required.

The taking lens has to be considerably longer than the ones used in the previous examples, 85mm is the widest you can go on a full frame sensor to avoid side vignetting. When converting the focal length, this comes close to a 45mm on the horizontal axis.

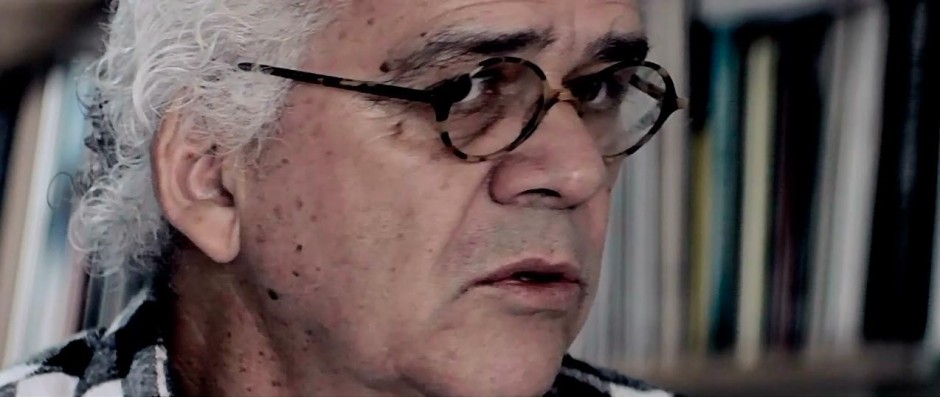

Henri Chrètien Hypergonar Hi-Fi 2 and its support system.

Another obstacle: none of these lenses have filter threads, preventing proper use of diopters to improve minimum focus. Some have clamps to hold filters, but in most of them we have to improvise a solution, like the Hypergonar Hi-Fi 2, to which I glued a 95-86mm step down ring to the front of the lens, allowing the use of filters with both diameters.

95-86mm step down ring glued to the front of the Hypergonar Hi-Fi 2.

Now getting to the more interesting part of this chapter: lenses for smaller projectors. Manufactured almost exclusively in Japan by Kowa and Sankor during 1970-80 and shipped out to the whole world, these lenses come in different shapes and sizes but they mechanism and performance are almost identical. Minimum focus is set at 1.5m and properly designed clamps and rings to attach filters onto either Kowa or Sankor.

The most wanted versions are Kowa 8-Z and Sankor 16-D that used to be the high end versions of the smaller ones. It’s quite common to find these very same lenses with different labels – Eiki, Elmo, Vidoscope, D.O. Industries, Singer, the list keeps going – but their manufacturer was always the same, it’s just the name that changes.

Sankor 16-D plus clamps and accessories.

The 2x stretch makes the anamorphic bokeh very pronounced when using these lenses, but 16:9 video ends up with a ludicrous 3.56:1 proportion – a little image strip in the middle of a black screen. The best workaround for this issue is to shoot 4:3 as RED cameras in Anamorphic mode, or the Alexa 4:3, Canon DSLRs through Magic Lantern and, even more recently, the Panasonic GH4. This way the resulting image has a 2.66:1 aspect ratio.

Strong anamorphic flares and bokeh.

One of the differences between 35mm projector adapters and the smaller ones is the coating used on the glass. The 35mm ones are multi-coated since they’re modern lenses and this kills the anamorphic flares. On the other hand, the smaller ones are single-coated and present warm orange flares that can’t be achieved by any other way.

One of the most dreaded features introduced by projection lenses are the “anamorphic mumps” which first came to sight when Hollywood started using anamorphics and it’s still a common feature among the vintage models. David Bordwell explains it way better than I ever could:

“(…) the ‘squeeze ratio’ of Chrétien’s lens design varied across the horizontal axis. These optical tics created distortions and patches of soft focus. The most embarrassing flaw, created by faults in magnification and the uneven compression of the visual field, made central figures look oddly bloated. In close ups, the result was ‘CinemaScope mumps’. Not all of the films were shot with Bausch & Lomb lenses, but other brands of anamorphic lenses tended to cause the same problems.” (BORDWELL, 2007, p.288)

As Bordwell describes, the cause of this quirk is the uneven glass curvature related that creates the stretch factor. Around the edges of the lens the compression is stronger while in the middle the image tends to be more spherical-like. Stretch is not constant across the horizontal axis and also changes according to the focus distance. For objects that are further away, closer to infinity, stretch is 2x, but when the subjects come closer to the lens, this number can go as low as 1.7x. When this footage is stretched back to its “proper” aspect ratio whatever subject is in the center of the frame becomes wider than the real world version of itself, thus creating mumps.

Mumps on a close up shot using a 135mm taking lens + Kowa for Bell & Howell.

There are also exceptions and special cases, as double focus lenses with 1.5x stretch, designed for amateur 8mm and 16mm cameras, such as Bolex-Möller or Yashicascope. Because of their size, they’ve been kindly named baby anamorphics. As they exist in smaller numbers and from different manufacturers their optical quality vary greatly.

Taking these exceptions into account, the few double focus adapters that can be compared to Iscoramas, when it comes to image quality, are Kowa for Bell and Howell and the Bolex-Möller. The first ones, from Japan, were made specifically for an european projector company (Bell & Howell) that demanded extensive quality tests, so this brand of Kowas can be set apart from the other ones.

Kowa for Bell & Howell with Redstan clamps.

Bolex-Möller are germans and, as the name indicates, they come from a partnership between the camera maker Bolex and Möller optics, which means these are lenses for shooting, not projecting. Their minimum focus is at 0.5m. There are two different versions of Bolex-Möllers: one for 8mm and the other for 16mm, considerably bigger. After a while, the partnership ended, but Möller still made some more anamorphics on their own. Even though the markings are different (they don’t say “Bolex” anymore), the optical quality is identical.

2x stretch is only achievable through thicker glass elements. Because of this extra thickness, another problem comes to life: while using DSLRs, depth of field can be so short that it doesn’t cover the whole thickness of the anamorphic glass. In this situation, the center of the image is in focus, but there’s a mismatch between vertical and horizontal fields on the edges of the frame, reducing image quality.

Taking this into account, in order to shoot good quality footage it’s better to work with smaller apertures which grant enough depth of field to cover not only the center of the adapter. Apertures between f/4-5.6 tend to have great results. The issue makes it harder for this kind of lens to have decent performance while shooting in low light conditions.

PROS:

– Very strong anamorphic bokeh;

– Lower prices than the other anamorphic adapters;

– Minimum focus between 0.5m and 1.5m (for older lenses);

– Strong flares (for older lenses);

– Great image quality from edge to edge (for modern lenses).

CONS:

– Double focus: it’s necessary to focus both the taking lens and the anamorphic at the same distance so the image is sharp in the camera;

– Too big and heavy (for modern lenses);

– No filter threads;

– Minimum focus is too far (for modern lenses);

– Taking lens aperture must be between f/4-5.6 for better performance;

– Camera must be fixed because racking focus is a nightmare;

– Mumps and distortions across the frame;

– 3.56:1 aspect ratio, way too wide for anything practical.

You must be logged in to post a comment.