< < BACK TO CHAPTER VI - THE PROCESS

VIA – CONCEPT DEVELOPMENT

Starting with Episode 01, it takes a lot of imagination on the actors behalf to put themselves into the context of this ruined environment that visually goes no further than the minds of the crew. In this sense, shooting with a digital camera allows for smaller and lighter gear, decreasing any distractions that might come from a large crew walking around and a noisy huge film camera. Besides, a lighter camera provides us with great mobility and versatility when setting up shots and capturing any improvisation or coverage that wasn’t planned on the call sheet.

We planned to use Canon’s 5D Mark III for a number of reasons, but they were all dropped when the LOMOs were unable to cover the full frame sensor. We had to go with an APS-C sensor camera. The choice was Canon’s 50D and it’s quite an unusual choice because, even though it’s a strong camera, released in 2008, it wasn’t even supposed to record video.

The greatest feature about the 50D is, due to the enhancements provided by MagicLantern (better explained in Chapter 4 – MagicLantern), this camera was able to beat newer cameras in raw recording because it uses a Compact Flash card instead of the now-standard SD cards, which are much slower by comparison. Compact Flash cards achieve the best results for raw recording for their huge write speed.

Some of the visual and mood references we wanted to achieve through cinematography for Episode 01 come from the game The Last of Us (2013), and some of the jungle sequences from Hunger Games (2012). In both cases, lighting is absolutely realistic – the light is diffuse and doesn’t have so much contrast between the highlight and shadow areas.

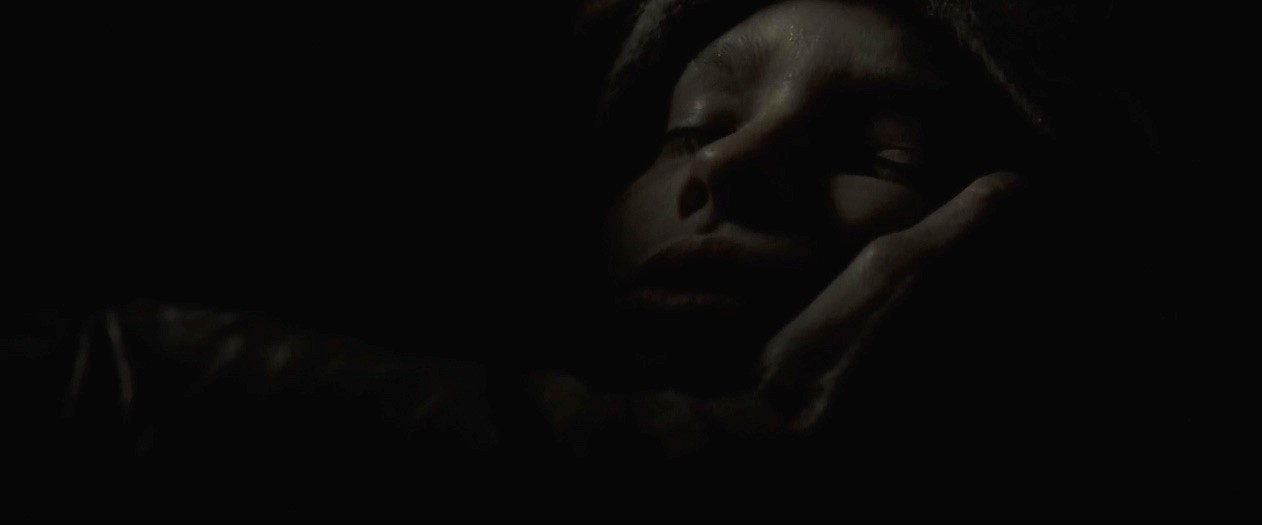

As references for framing, our sources were the movies The Book of Eli (2010), I Am Legend (2007) and some sequences from The Road (2009), which make great use of dynamic compositions between background and forefround in order to create tension. A good example of this feeling is the first frame below, from The Book of Eli, where something is happening on the background but all the attention is focused on our character’s face at the foreground. At the same time, they compete visually and it’s hard to stay on his face for the whole shot, going to background and coming back to check his reaction. They complete each other in terms of meaning.

From top to bottom: The Book of Eli, Hunger Games, I Am Legend and three frames from the game The Last of Us.

Since each episode was shot entirely separate from the other, with a budget of only US$75 for each, we didn’t get any proper lighting gear of even electricity running on set. All of our light variations were based on the Sun’s position, carefully picked daytimes for each sequence and delicate handling of the raw files during post production.

The great brightness also allowed us to work at smaller apertures, bringing more information to the background of each shot, not only an indistinct blur, which helped visually in the sense of creating this world we had in mind, of a city abandoned by men and taken back by nature. We had to keep the camera running at lower ISOs since it didn’t handle noise all that well (we tried to be below ISO640 at all times, going above that only it was absolutely important) – the 50D is quite old already.

Episode 02 on the other hand plays at night, is dark and much more tense than the first part. Because of this, cinematography requires lots of contrast. Based on this, we had numerous practical lights on set – such as torches, a real diegetic campfire, and LED flashlights to create rimlights around the characters, representing moonlight. Since a lot of our lighting relied on real fire, I worked very closely with the art department to intensify or lessen the flames according to each shot, achieving a stylized look, still quite realistic, with great shadow areas in every composition.

In order to keep the camera feeling from the first episode, we didn’t use a single tripod or any other support gear but the shoulder mount, giving me freedom to try long camera moves as well as creating a constant camera shake which works well for tension and increases the realism feeling we wanted for the series, coming closer to a documentary shooting style.

Episode 02 is strongly based on the relationship between the characters, which leads us to more close up shots and reactions than big camera movements or wide shots. With this approach we increase the tension about what’s around them at the same time we capture the essence of their acting and their point of view, by going so close.

Some of the references for framing, lighting and mood come from the movies Doomsday (2008), Hunger Games (2012) and, mainly, The Road (2009).

From top to bottom: Doomsday, two frames from Hunger Games, and three frames from The Road.

It’s not a joyous and colorful look but it brings a great complimentary color scheme between the strong orange from the flames and the blue moonlight taking turns between the most bright areas in the shot. In this regard, Episode 02 is the very opposite of Episode 01: no sunlight at all, it’s key lighting is a very warm campfire and most of the lighting is practical along with a couple flashlights so we can change framing quickly without moving light stands and such.

I’ve written about the lens choice for this episode on Chapter VB – Iscoramas, and fortunately we didn’t have any unpleasant surprises.

You must be logged in to post a comment.